CPH’s front entrance welcomes you to a number of services, departments and professionals that address the peninsula’s health care needs.

Central Peninsula Hospital is a home-grown product. What we see today as the main engine of medical care on the Kenai Peninsula began small—an idea germinated by a small group of peninsula residents. After a long, complicated dream-to-reality process, what was then called Central Peninsula General Hospital opened and immediately established itself as vital to the peninsula’s growth and health. From its modest beginnings 50 years ago, the hospital has expanded its footprint and its services to become the cornerstone of the area’s medical establishment and the emblem of health care on the Kenai.

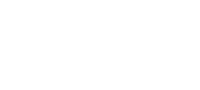

Cheechako News image showing the cornerstone of the new hospital being laid.

Left to right: Alaska

Gov. Bill Egan, Dr. Paul

Isaak, architect Linn

Forrest and contractor

Robert Clay.

One of the earliest notions of an area hospital occurred in early 1958 when the Kenai Civic League announced that its recently established Hospital Committee was exploring the idea of building either a medical clinic or a hospital to serve “the greater Kenai area.” At the time, the central peninsula had never had a resident physician, and the nearest full-service hospital was in Seward. There were non-surgical hospitals in Homer and Seldovia, but the increasingly populous central peninsula itself was ill-equipped for emergencies and even general health care.

Every Friday, either Dr. Joseph Deisher or Dr. Paul Isaak would travel from Seward and see patients in the back lobby of the Harborview Hotel on the Kenai bluff. Local residents could make reservations by telephoning Ruth Hursh at nearby Wildwood Army Station. Kenai’s first resident physician arrived in town later in 1958 and stayed for two years. It was nearly three more years until the second one, who stayed just over a year, and two more years until the third. Meanwhile, in Soldotna a group of entrepreneurs financed and built a 32-by-50-foot medical clinic and enticed Dr. Elmer Gaede and Dr. Isaak, plus dentist Dr. Calvin Fair, to move their practices there in 1961. In that first clinic, Isaak and Gaede practiced mostly general medicine but also delivered dozens of babies and performed minor surgeries. Emergencies and more complex surgeries were ushered to Seward or Anchorage. The land for the clinic had been purchased from homesteader Joe Faa, who also later sold the land upon which the hospital was erected. In fact, most of the central peninsula’s current medical infrastructure now stands upon former Faa land.

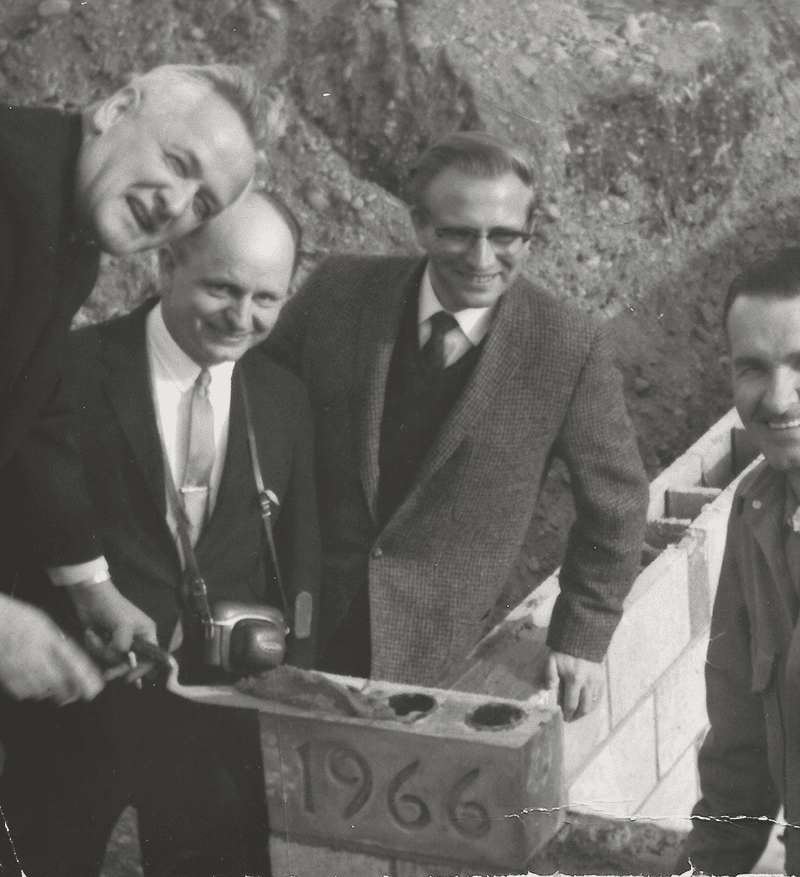

Joe Faa with horse “Danny” around 1961.

Hospital site land was purschased from Joe and “Mickey” Faa.

Almost as soon as Isaak arrived in Soldotna, he initiated a drive to create a hospital. In December 1960, at a meeting of the Soldotna Chamber of Commerce, he “reported on progress of the movement for a Kenai- Soldotna area hospital.” By mid-summer 1961, that movement was official. On July 24, at meeting held in a

classroom in the tiny Soldotna School, a grassroots, multicommunity group formed the Central Kenai Peninsula Hospital Association. Interested citizens began seeking

funding sources and a suitable location for the facility that many assumed would be up and running by 1964.

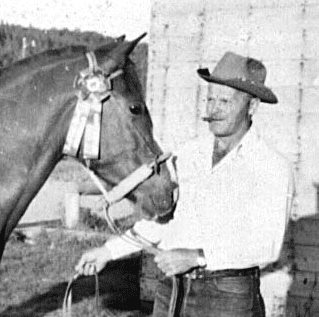

Groundbreaking with bulldozer:(L-R) Grocer Bob Wilson, Entrepreneur Clarence Goodrich, Grocer Doyle Jowers, Entrepreneur Burton Carver, Homesteader Jack Farnsworth and Dr. Paul Isaak.That’s a D8 Caterpillar in the background.

Instead, the effort required 10 years—a decade rife with financial snafus, contract disputes, bitter intercommunity fighting, and delay after delay, including the 1964 Great Alaska Earthquake. Over this decade, progress was erratic: Several Soldotna-versus-Kenai skirmishes over location delayed a final decision until 1965. Although a ceremonial groundbreaking occurred in September 1965, the actual breaking of the ground with bulldozers happened in March 1966, and the cornerstone was laid in September 1966. The hospital was judged about 70 percent complete by mid-winter of 1966-67, but major funding issues stalled and then halted construction by 1968. The Kenai Peninsula Borough stepped in, and by 1969 a hospital service area had been established. By the time old debts had been paid, the borough had assumed ownership of the hospital site, and a new architect and contractor had been signed, the unfinished hospital had stood empty for nearly three years. Since the borough was not in the hospital-operating business, the Lutheran Hospitals and Homes Society of America assumed control, with E.E. “Gene” Wheeler as its first administrator. A public dedication for Central Peninsula General Hospital was held June 12, 1971, and an obstetrics case became the facility’s first patient 14 minutes after officially opening its doors on June 21.

As conceived when construction began in 1966, CPGH was going to be an 8,000-square-foot building.

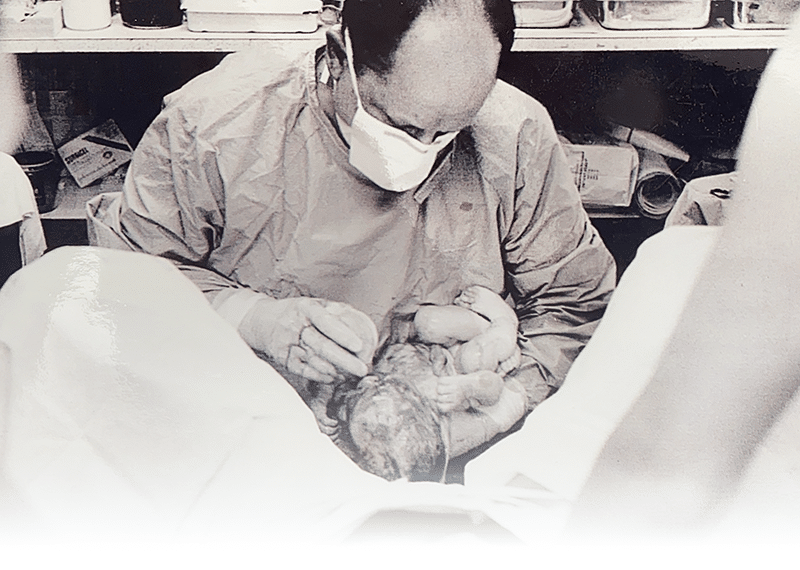

Dr. Paul Isaak delivers the newest member for a Kenai Peninsula family.

A new architectural firm and a new contractor changed that. Including the basement, the hospital opened as a 17,480-square-foot facility. The opening-day staff included director of nursing Pat Severe; anesthesiologist Alfred Gelinas; and four staff physicians: Dr. Isaak, Dr. Gaede, Dr. Elaine Riegle and Dr. Peter Hansen, joined in August by the peninsula’s first surgeon, Dr. Joseph Sangster. The hospital itself consisted of nursing and surgery departments, radiology and a lab. Support services included laundry, dietary, housekeeping, and business and administration offices. The first hospital staff included 15 registered nurses, six licensed practical nurses, two laboratory

technicians, one x-ray technician, and about 20 auxiliary personnel. Wheeler said the hospital, with a daily room rate of $70, was expecting about 50 percent occupancy for a while. He also expected hospital payroll alone to pump at least $30,000 to $40,000 a month into the local economy.

At the end of the first pay period, the hospital issued 52 time cards, and its actual monthly payroll for 1971 was $53,780.

The number of patient visits and the hospital itself grew steadily. In about the first two weeks of operation, CPGH handled 53 emergency room cases, served 14 obstetrics patients and delivered four babies—a total of 71 patients. During 1972, its first calendar year of operation, the hospital had 3,185 patient visits. In 1990,

the last full year before the facility’s 20th anniversary, patient visits had increased to 23,350 and the hospital’s footprint had expanded to 101,000 square feet. Then administrator Mike Lockwood told the local newspaper,

“We’ve grown a lot, but I’m not sure bigger is always progress. I define it as continual quality improvement. That means we try to do the things we do better. Sometimes that means added services. Sometimes it means improved technology or just doing things with more sensitivity.”

Finding parking close to the entrance was a little easier in these early days, though it wasn’t always smooth going.

In the 1970s, hospital service area voters expanded the powers of their board to allow for the establishment and operation of an alcoholism-treatment center. They also approved a $6.7 million bond sale to expand and renovate facilities that hospital staff was already outgrowing. In the 1980s, just as the Phase One expansion was being completed, service area voters approved a second bond sale, this time for $5.7 million, to fund yet another expansion and renovation. When both phases were

complete, CPGH had a new emergency room, x-ray and lab facilities and administrative offices; the surgery and obstetrics facilities had been expanded, and more beds had been added. The hospital had also added three new services—ultrasound, respiratory therapy and alternate birthing.

By the 20-year anniversary, CPGH had its Family Recovery Center and a new CT 9800 scanner, and had expanded its emergency department from its original

configuration of one room, one bed and one examining chair to an 11-bed facility. The number of beds at CPGH had risen from 32 to 62, the number of physicians from four to 25, the number of nurses from 15 to 59. But much more change loomed on the horizon. The agreement with Lutheran Hospitals and Homes Society

of America expired at the end of 1992, and the borough supported the formation of a new nonprofit corporation (CPGH Inc.) to lease and operate the hospital.

The 2003 Mountain Tower begins to rise above the original hospital footprint and significantly expand the services offered.

Borough Mayor, John Williams joins the staff at CPGH for the ribbon cutting, opening the Mountain Tower addition to hospital’s campus.

After this, the borough itself separated from the new corporation and established an elected Service Area Board to guide CPGH Inc. In 2003, service area voters again voted with their pocketbooks, approving a nearly $50 million bond sale for a massive expansion and renovation. The grand opening for the facility—with its Mountain Tower and renamed Central Peninsula Hospital—occurred in 2008. Nearly 50,000 square feet of the existing complex had been remodeled. By the time the River

Tower, a new Catheterization Lab and Obstetrics Unit had been completed, the entire hospital had grown to 320,351 square feet. In 2020—the most recent calendar

year completed by CPH—the total number of patient visits for the hospital and all its related facilities was 160,628. The hospital’s monthly payroll had vaulted to nearly $7 million. By 2011, the hospital was making the entire bond payments on behalf of taxpayers and is still making these payments today, thus saving service area residents more than $32 million dollars in taxes they had vote for themselves. In short, since 2011 the hospital has collected no taxes from taxpayers to operate the hospital.

Several important factors, including population growth, contributed to the expansion in the 2000s: The central peninsula needed a hospital better able to provide services for an aging population. The hospital needed to provide medical access to residents who were being shut out due to insurance issues. And the entire facility needed an upgrade, moving from a hospital capable of providing basic needs to one ready to face the future and supply major medical services that hadn’t been available locally.

When the hospital opened in 1971, the median age of borough residents was 26; by 1991 the median age had climbed to 31, and in 2021 it is 41, increasing the need for services directed toward seniors, toward cancer treatment, and toward a philosophy of allowing patients to receive full medical care without having to leave home—in other words, to remain closer to their families and support systems. In 2021, more than 80 percent of the patients at CPH are age 50 or older.

Connected to the aging population on the Kenai was the inevitable “silver tsunami” of baby boomer retirements. In the early 2000s, many retiring residents began to

find themselves in a changing insurance environment, especially when they made the switch to Medicare at age 65. Some medical providers, unable to survive

financially if they took on too many Medicare patients, began capping the number of such patients they would accept. Many patients, after decades of familiarity, were

forced to seek new providers. Starting in 2009 with family practice services, nonprofit CPH then became one of the few hospitals in Alaska to open primary care clinics that accepted Medicare. The Medicare insurance access problem on the central Kenai disappeared. As these clinics were being established, CPH began recruiting private specialty physicians—in areas such as cardiology, radiation oncology and spine—further increasing the access for borough residents who now rarely

have to travel away from home to receive medical services. In addition to family practice, CPH owns clinics that specialize in pediatrics, urology, orthopedics, neurology,

OB/GYN women’s health, surgical podiatry, internal medicine, oncology, urgent care and general surgery. Although this model of patient care is rare in Alaska, CPH

officials believe it is particularly adept at providing access to those who are uninsured, underinsured or on Medicareor Medicaid.

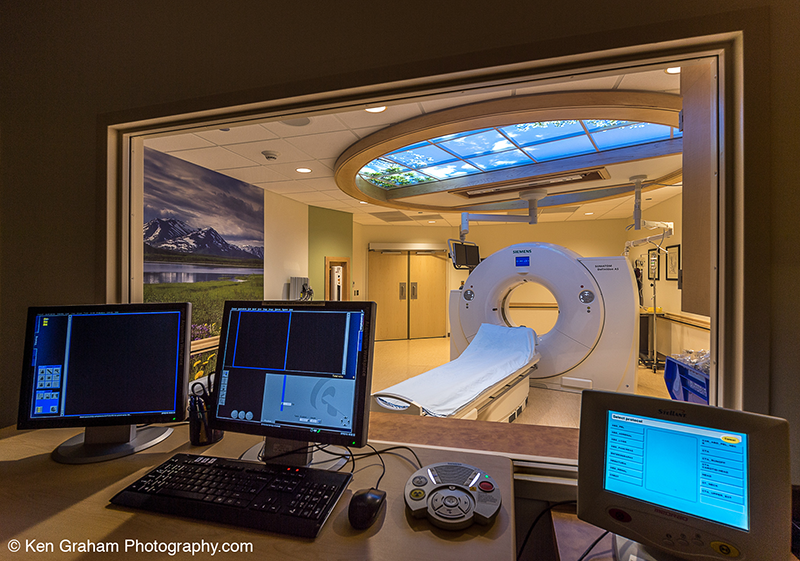

During the 2005-2008 expansion and renovation, the Mountain Tower, with its vastly updated technology (CT, MRI, Women’s Imaging Center etc.), became the base

around which everything else evolved. Its modernized medical/surgical unit (Med/Surg), Intensive Care Unit (ICU), pharmacy and operating rooms provided a facility that attracted physicians to

the area and allowed the remaining expansions to occur. In addition, CPH instituted a “hospitalist” model that provided physicians around the clock, thus improving the consistency and quality of care and allowing primary care physicians to focus more on their in-clinic patients without having to be on call at the hospital 24 hours a day. During the construction of the Mountain Tower, CPH also became a base station for

a round-the-clock air-ambulance helicopter. Prior to this, a helicopter or fixed-wing plane had to be called in from Anchorage.

The next phase in bringing specialty care to residents was the River Tower, which opened in 2016 and focused on allowing patients to remain in their community while

receiving medical services. The River Tower housed the much needed Cancer Treatment Center—radiation oncology, infusion services and medical oncology—

The generation that initiated the efforts to make the hospital a reality, now were reaping the fruits of their labor, as the aging population pointed the way for the hospital to expanded once again.

Overseeing the construction of the newest expansion.

services that for the most part hadn’t existed on the Kenai. CPH had had a fledgling infusion clinic that literally began in a closet. The closest place to receive radiation treatments had been in Anchorage, where patients needed two weeks of daily 20-minute treatments. Some patients drove back and forth to Anchorage every day for two weeks or spent the two weeks in Anchorage hotels—burdens no longer necessary. At River Tower, patients can receive daily radiation treatments, returning to work or home every day and sleeping in their own beds. The remainder of space in the River Tower is for both independent and employed specialty physicians— mostly surgeons who need and prefer to be on the hospital campus—and the imaging and diagnostic components and physical therapy that support these services.

The most recent changes at CPH have included the relocation of the obstetrics (OB) area and the completion of the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory, with its diagnostic

imaging equipment to allow physicians to visualize the arteries and chambers of the heart and more effectively treat any abnormalities. Prior to the installation of the Cath Lab, all patients requiring this service had to travel to an Anchorage hospital; now only a small percentage requiring specialized care find it necessary to leave. OB services, now adjacent to Med/Surg, had long been stationed in the original part of the hospital. The new OB unit was designed not only for labor and deliveries, but also as an overflow area for the Med/Surg unit. When Med/Surg and ICU are full, the OB unit, with its four beds accessible from Med/Surg, can handle the overflow while keeping the remainder of the OB unit secure.

CPH’s front entrance welcomes you to a number of services, departments and professionals that address the peninsula’s health care needs.

The envy of many Alaska communities is the CPH Behavioral Health Department and its three linked facilities that provide help in the battle against the destructiveness of substance abuse on the Kenai Peninsula. The trio of facilities—Care Transitions, Serenity House Residential Treatment and Diamond Willow Transitional Living—have been developed over time through grant funding from individuals, foundations , businesses and the State of Alaska. Care Transitions is a six-bed, withdrawal treatment facility focused on helping individuals through the physical and psychological effects experienced once they stop using. Serenity House is the next step for many as they begin their recovery. And Diamond Willow can provide recovering clients with a safe environment in which they can stay sober and learn life and job skills. All clients are able to participate in intensive outpatient therapy and then step down to a less demanding outpatient treatment.

In the early 1960s, Dr. Paul Isaak led the charge to help people requiring medical services to remain in their own community rather than face the arduous, often lonely challenges associated with transportation to and treatments in hospitals elsewhere. After a decade of struggle, the dream of a central peninsula hospital was realized, and in the subsequent half-century services continually improved, making Central Peninsula Hospital arguably the greatest investment ever made in the residents of the Kenai. Today CPH stands as a modern marvel, with a medical staff second to none anywhere in the state. As a truly “community” hospital, CPH will continue to provide services and the attention locally that its patients need and deserve.

Serenity House Residential Treatment facility continues the tradition of healing that started it’s journey in the 60s and now continues into the next 50 years.